-

video - Aleksandra Oilinki

artwork photography - Jussi Tiainen

music - Aleksandra Ionowa, excerpts from album Improvisations for grand piano (1978), Courtesy of Ionowa society

-

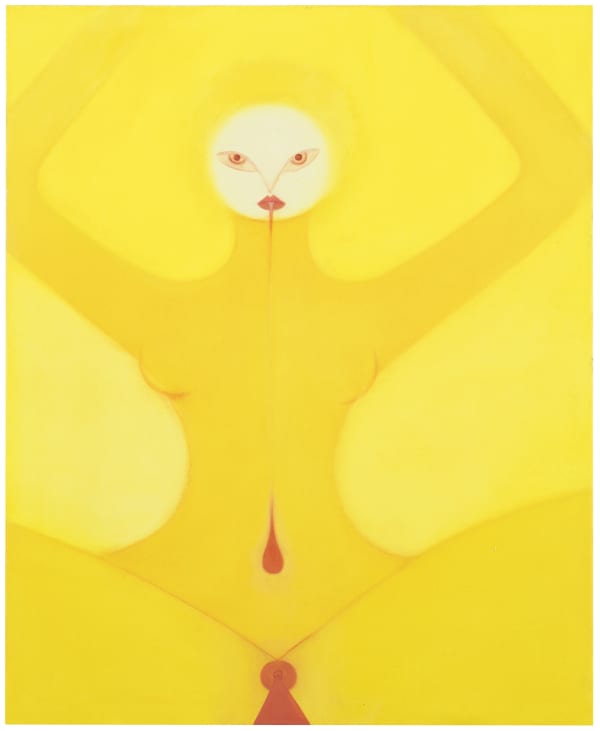

Mari Sunna, Eremites, 2021

-

The limitations of form aren’t simple to abandon, not least because they exist somewhere deeper, pulling strings in the subliminal layers of our minds. Mari Sunna’s approach to solve this is to install a set of her own, conscious boundaries for example by focusing on symmetry, static dynamism of composition, or through automatic painting. The geometry and mathematics push the painting process towards the automatism of the brushstrokes, by eliminating learned gestures (disguising themselves as natural) and giving way to something rising from the unconsciousness, to something that could perhaps be characterized as a form of true freedom.

This pursuit for freedom of expression is present also in the works of some of the artists Mari Sunna has been inspired by lately. In the artmaking of visionaries, such as Aleksandra Ionowa (1899–1980) or Guo Fengyi (1942–2010), the spirituality of their art and the images they produce seem to materialize more directly from somewhere inside them, without the boundaries created by formal artistic education.A more analytical source of inspiration for Sunna has been the collaboration of Grace W. Pailthorpe and Reuben Mednikoff, that resulted in a vast collection of experimental psychorealist paintings resembling visually the surrealist paintings of that same era. Pailthorpe, a surgeon turned psychoanalyst, joined forces in the 1930s with a poet and painter Mednikoff to create images rising directly from the subconscious. The paintings and drawings were then subjected to psychoanalytical interpretation and read as pure manifestations of the subconscious mind. The goal was, through the interpretive analysis of these mental images, to liberate individuals from constraints holding them back, and to achieve free expression of the unconscious – true freedom.

In Mari Sunna’s works, too, one can find compositions stemming from mental images and a sort of carnal corporeality, playful and immensely sensual at the same time. In other paintings, a more centred, symmetrical approach fixates the focus on a gesture, an expression or a glare. Sunna seems to stretch the figures to the limits of their existence: she is indeed interested in taking form itself to unusual places. In the painting Eremites, the figures can be characterized as figurative: we can perhaps spot an eye, a slender neck, maybe an open mouth, but none of them are exactly easily identifiable, their characters still strange enough to stir our imagination.

There’s a plurality of atmospheres present – from the soft, ethereal calmness of the barely-there female characters to the more aggressive figures with their sharpened nails and fangs, glaring at us as with an intensive, almost menacing stare. Others seem to fill the surface of the canvas with only barely recognizable features, evoking in a viewer a sense of familiarity as well as bewilderment. There are no clear-cut interpretations – a fact, that forces the viewer to reflect their own inner worlds, to react with the painting. There is always present a certain tension and an intensive presence, although in a form unattainable to us, somehow underlining the otherness of whatever it is we connect with in the painting.Mari Sunna’s paintings are not born through linguistic processes, but by explicitly avoiding them, and as such they don’t readily submit to written articulation. Sunna’s works strive to achieve something that isn’t easily captured, explained, or returned to a simple form. An expression that refuses to conform.

Aleksandra Oilinki

-

Mari Sunna, Family, 2021

-

Mari Sunna, Care, 2021

-

Mari Sunna, Untitled, 2019

-

Mari Sunna, Perfume, 2021

-